Catching rays: a research experience in Costa Rica

Spending the summer of 2024 with the NSF-IRES Costa Rica program, Baylen Ratliff wasn’t just catching rays of sunshine. He spent three weeks in Costa Rica observing estuary rays, exploring coral reef ecology, and recording humpback whale songs. The NSF-funded program took place in Santa Elena Bay, located on the northwest Pacific coast of Costa Rica, a Central American country known for its biodiversity, both in its vibrant rainforests and sparkling waters. Baylen, a UW Marine Biology senior, shared his four-week research experience with us, from what he worked on, new skills he learned, and how he found out about the opportunity.

You spent three weeks in Costa Rica with the IRES Program – what did your experience entail?

The program involved so much! It was broken down into three different themes, each directed by a different mentor and expert in that particular field. The first theme was elasmobranch movement patterns (sharks and rays!), where Dr. Mario Espinoza (University of Costa Rica) and Diego Fallas (University of Costa Rica) got us snorkeling in the water every day in Santa Elena Bay, netting, measuring, and tagging estuary rays. The second was coral reef ecology, health, and restoration, which we conducted through SCUBA diving with Dr. Juan Jose Alvarado (University of Costa Rica), Dr. Cindy Rodriguez (University of Costa Rica), and Fabio Quesada-Perez (University of Costa Rica). The last theme was cetacean acoustic monitoring, where we were led by Dr. Laura May-Collado (University of Vermont) and the field assistants Franny Oppenheimer (University of Vermont) and Ilaria Coero (University of Vermont) in recording the songs of humpback whales, while monitoring their behavior around the bay. Cetaceans are marine mammals such as whales, dolphins, or porpoises.

For each of these themes, we got a special presentation from the mentors involved detailing their projects and their importance in the area. We also got to learn and practice skills necessary for proper animal handling and data collection, helping us to be efficient in the field. Another essential part of this program were the multiple statistics and R programming workshops, directed remotely by Dr. Joaquin Nunez (University of Vermont). As someone without experience in stats, these gave me a great handle on how to use R in new ways, how to design statistical methods, and the best ways to run data for a variety of projects.

Altogether, the program touched every piece of what it means to conduct field work in a tropical environment, how to tackle research on small vessels, deal with unforeseen problems as they come, and how to process and utilize your data when it’s all done. I also made great friends with the graduate and undergraduate students of the program, and am grateful to have met and learned from each of them.

A typical day would involve rising sometime around 7am and enjoying prepared coffee, fresh fruit, and breakfast with the team. Most days, we loaded trucks with the necessary equipment (sometimes for SCUBA, sometimes for snorkeling, and sometimes just note sheets and hydrophones) and drove off to our launch-point before 9am. Our partners at Diving Center Cuajiniquil, located in a small fishing village in northwest Costa Rica, would dock our two research vessels while we transferred all of our gear onto them. Students would split into teams, with each boat having a guiding mentor/team lead as well as an operator for the boat. Then we were all set for the day!

For the next 5-7 hours, we lived on the sea. Some days, we would be in the water for a few hours tracking down rays, others we set up longlines with fish bait so that we could wrangle up nurse sharks and tag them with monitors. All of that hard work in the sun requires rest, and we had fantastic, refreshing prepared lunches every day. The best days were when we could stop off on a beach and enjoy our lunch, fruit, and sweet tea before getting back to work.

At the end of the day, we would return to the hotel, ideally before getting caught in the predictably rainy afternoons. We mostly made it on time! As all good researchers should, we would wash off our gear, set it up to dry, and process what data we collected that day. Over afternoon coffee and snacks, we talked about the day, what we saw, what we learned, and what we were curious about.

Importantly, this experience was fully paid for. Each student’s travel was covered through the program, as well as a stipend for four weeks of work (three of which were spent in Costa Rica). After returning from Costa Rica, the program requests a one-page research proposal relating to any of the themes in the program. My proposal covered the methods for a Marine Protected Area impact survey to deliver across the northwestern province of Guanacaste, to help get a sense of what perspective community members have on MPAs in their area and the impacts on their livelihoods. Following these initial four weeks, there are opportunities to remain involved, with the program designed to allow long-term commitment for students interested in particular parts.

What drew you to this opportunity?

I had never conducted research outside of Washington State, and wanted to gain experience in a vastly different part of the world where conservation science and community interests blend uniquely together. Particularly, I was drawn in by the opportunity to work directly with shareholders in the community, which we did nearly everyday alongside avid divers from Diving Center Cuajiniquil.

Aside from research, all of my education has focused primarily on temperate aquatic environments. I saw this opportunity as a way to break outside of this shell of knowledge, and to expose myself to something new. This was a little scary to do, especially considering I had no Spanish speaking background, but this is the exact kind of student this program wants to involve. I felt wholly supported in my participation, and while it may be a little embarrassing to only speak English, there are invaluable learning opportunities in taking the plunge to invest yourself into a different community.

- A King angelfish hanging around a coral restoration structure (Holacanthus passer). (Credit: Fabio Quesada-Perez).

- A small crab hiding amongst the coral. (Credit: Fabio Quesada-Perez).

- One of many sea turtles we spotted on the surface during our excursions. (Credit: Ilaria Coero).

- A Mangrove Ray in Santa Elena Bay (Credit: Steven Lara).

What was a highlight for you during the program?

Hands down, the most exciting portion of this program happened during the cetacean monitoring week. On one of the last days of field work, the team got up bright and early at 5am to make the most of the clear weather. After preparing our gear and loading onto the boats, we set out, scanning to open water for any whale activity. Everyone is tired. There is a light drizzling of morning mist as we glide through our first minutes on the water. Suddenly, my eyes catch movement. A half mile away, a humpback whale calf has breach outside of the water, just above its mother. “Breach!” I reactively exclaim, as others have yet to notice. Heads turn. Within seconds, our boat is heading towards the mom and calf. We scramble to get our note sheets together as the boat rocks under the sudden acceleration. I jot down GPS coordinates while my friends prepare the camera and yell out the whale’s behaviors. Whenever I think of my time in this program, this is the morning that reminds me why I feel a calling to marine research. Experiences like this do so much to affirm my pursuit of a degree in marine biology, and I look forward to others sharing these joyful and wondrous moments unique to our field.

- The dorsal side of a humpback whale that we monitored during the cetacean week.

- The morning when we saw these whales reminds me why I feel a calling to marine research.

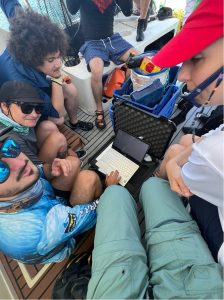

Another highlight of the program was when we were directed to develop methods for mapping the sediment composition of Santa Elena Bay. We were given free reign on what materials to use, how large of an area to capture, and what classes of sediment to identify. Ultimately, we chose to lower a GoPro camera while systematically labeling each video of the seafloor. We moved around to different pre-selected GPS coordinates and were sure to maintain a consistent distance for each shot. This was the closest I have ever come to being my own project lead. Collaborating with each of the other students to answer a research question and solve all of the technical and methodological problems involved was exciting, and extremely rewarding.

Had you ever been to Costa Rica before?

I had never been to Costa Rica before, and had never been further south than the Pacific coast of Mexico. This was an entirely new experience, academically, professionally, socially, culturally, and environmentally. This program took place over four weeks – three of them in Costa Rica – and while it may seem short on paper, the experience was so full of memories that I could never hope to scratch the surface of it in a single blog post.

What’s next for you in relation to this research experience?

The PI’s and mentors are committed to the long term support of this program and the success of its students. I plan to return to Costa Rica in the near future to assist in a variety of projects, both through research and potentially as a field assistant.

How did you find out about the opportunity and what was the application process like?

I found out about this opportunity through my 2023 REU-Blinks Mentor, Dr. Olivia Graham. She had found the application and information page on Twitter posted by one of the original PI’s for the program. Seeing as it was something that lined up directly with my interests and would be a deep dive into systems I had no experience with, it was an easy choice to apply. The application was fairly quick! As this was the first year for the program, applicants were asked one or two short questions about our interest in the program, which theme we were most invested in, and other questions about our experiences with diving, Spanish, and past research.

I was not expecting to be accepted: I had only a basic diving certification, had no experience speaking Spanish, and had no background in any of the themes. I was absolutely thrilled when I got my acceptance email, and I hope that others who may feel as doubtful as I did still choose to apply in future years.

- Cleaning off our SCUBA and data collection gear after one of the coral reef restoration days. We would do this after every trip to ensure our equipment stayed safe and usable, which kept us organized for the next morning.

- Group photos of the elasmobranch team during lunch breaks.